Photo: Raskrinkavanje.ba

In a series of articles that will be published in the coming period on the Raskrinkavanje platform, we analyze the narratives that have been spreading in the Bosnian and the Western Balkans region media since the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

In the early morning hours of February 24, 2022, the Russian Federation’s invasion of Ukraine began with an attack on several cities. At the time, Russian President Vladimir Putin called it a “special military operation” whose goal is “the denazification and demilitarization of Ukraine”. Soon after, in addition to a series of repressive measures against the media, a law against the spread of “disinformation” was adopted in Russia, which prohibited the use of the terms “war” and “invasion” while describing the attack on Ukraine.

The state censorship directives in Russia were voluntarily adopted by numerous media in the region, most often those close to the policies of the ruling parties from Serbia and Serb-dominated administrative region in Bosnia Republika Srpska, as well as media of similar ideological orientation in Montenegro. With more or less open support for the Russian Federation’s aggression against Ukraine, the pro-Russian media in the region at the same time avoided calling the war by its right name, using terms such as a “counter-offensive” and “special operation”. The work of the Serbian edition of Sputnik, a media outlet owned by the Russian government, which has been recognized in various research papers as a frequent source and distributor of political disinformation, contributed significantly to the copying of Russian narratives in the media in this language region.

Disinformation certainly flooded the media and social networks in the local language when the attack on Ukraine began. In addition to recognizable terms from the repertoire of Russian war propaganda, inaccurate claims and stories aimed at supporting Russia and “denigrating” Ukraine, the EU and NATO easily fit into the narratives that have been present in the region for years. The glorification of Vladimir Putin, the glorification of Russia and/or the satanization of the “West” have long been present in various ideologies in the region – from ethno-nationalist, which support the authoritarian personality cult of Vladimir Putin, to some left-wing circles, in which criticism of imperialism is directed exclusively at Western countries and alliances.

In the past ten months, we analyzed dozens of pieces of disinformation that were used to build and “support” narratives derived from the war propaganda of the Russian Federation. Six months after the beginning of the Russian invasion, together with partners from the SEE Check regional network we made an overview of the most common disinformation, their narrative frames, as well as the sources that spread it in the region. Now, almost a year since the beginning of the invasion of Ukraine, we present an overview of the most represented narratives of Russian war propaganda in BiH and the region in a series of analyses that we will publish here in the coming days. Here, we will look back at the chronology of the events that preceded the Russian Federation’s attack on Ukraine, and the “twisted” versions of them, which are found in the narratives that we have seen in the past months.

What preceded the war in Ukraine: Relations with Russia after the collapse of the USSR

On August 24, 1991 the Parliament of Ukraine passed a resolution declaring the independence of Ukraine from the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). Ukraine’s independence was confirmed at the referendum held on December 1, 1991, when about 90% of voters voted for independence. The USSR formally ceased to exist on December 26, 1991.

Along with the declaration of independence from the USSR, Ukraine strengthened its relations with NATO alliance. In December 1991, Ukraine joined the North Atlantic Cooperation Council, which was created as a forum for dialogue and cooperation with former Warsaw Pact countries. In the years that followed, Ukraine and NATO continued to develop relations, but this country did not become a formal member of the Alliance.

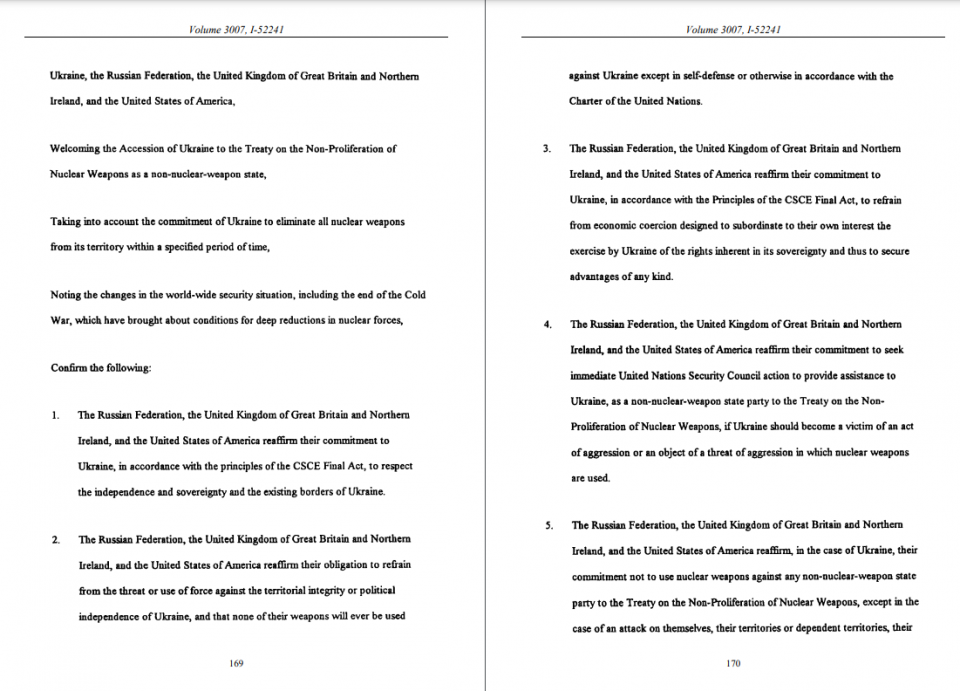

The next significant event in the relations between Russia and Ukraine happened in December 1994, when the Memorandum on Security Guarantees was signed in connection with Ukraine’s accession to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons in Budapest. With this agreement, Ukraine renounced the nuclear weapons it inherited from the USSR, while the Russian Federation, the US and Great Britain were obliged not to undertake any activities against Ukraine, including the use of force.

With this agreement, the nuclear weapons in the possession of Ukraine were transferred to Russia, which, for its part, committed to respect the borders, independence and sovereignty of Ukraine.

In the following decades, Russia did not make any incursions in Ukraine, but its political influence remained strong in that country. At the end of the 20th and the beginning of the 21st century, the polarization and mutual distancing of the pro-Russian and pro-Western parts of Ukrainian society became more noticeable.

In the presidential election held in October 2004, one of the candidates was Viktor Yanukovych, a politician close to Russia, whose candidacy was supported by Vladimir Putin. Yanukovych declared victory, but Ukraine’s Supreme Court ruled the election will be repeated due to allegations of electoral fraud. After mass protests called the “Orange Revolution” and a repeated vote, his opponent Viktor Yushchenko, who was poisoned during the election campaign but survived, won the election. Yushchenko’s policy was oriented towards Western integration, reflected in the efforts aimed at Ukraine’s membership in NATO, which Putin opposed. That is when the Russian state media started spreading conspiracy theories that “the West controls Ukraine” and that the ”Orange Revolution” was caused and led primarily by the US intelligence services (this is where the phrase “coloured revolution” originated from, which is also often used in the Western Balkans region to discredit civil protests as “staged”).

Photo: Flickr.com

The change of policy in Ukraine came in 2010 when Viktor Yanukovych was elected president. In November 2013, he refused to sign an agreement on closer ties with the European Union, which caused mass protests in which citizens expressed dissatisfaction with such a decision and asked for his resignation. The demonstrators camped at the Maidan Independence square in Kyiv and occupied the City Assembly and the Ministry of Justice. Protests known as “EuroMaidan” escalated in February 2014, when more than 100 people lost their lives. Yanukovych was eventually ousted and he fled to Russia.

How and when did the war in Ukraine start?

Russia responded to the protests and overthrowing Yanukovych by accusing the United States of directing the political events in Ukraine and by intensifying anti-West rhetoric and also the stories about the Russian population in Ukraine being threatened. These narratives served as a justification for the attack on the Crimea Peninsula which is inhabited by a significant percentage of the Russian-speaking population. After establishing control of strategic places on the peninsula, an internationally unrecognized referendum on “return to Russia” was carried out in Crimea, after which the Russian Federation annexed Crimea, which is still considered part of Ukraine in the international legal order.

At the same time, in the east of Ukraine, conflicts between Ukraine and the pro-Russian separatist groups began. Russia started supporting these groups, although it has denied providing them with state military support, claiming that the Russians who joined these groups did so as “volunteers”. On May 12, 2014, the rebels in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions proclaimed independence from Ukraine, calling these two territories the “Donetsk People’s Republic” and the “Luhansk People’s Republic”. In the armed conflicts between Ukraine and the pro-Russian separatists in the east of the country, more than 14,000 people lost their lives from 2014 to early 2022. At the time, the West imposed certain sanctions on Russia.

In September 2014, Ukraine and Russia signed a document known as the Minsk agreement. The provisions of this agreement implied the exchange of prisoners, delivery of humanitarian aid and withdrawal of heavy weapons. However, shortly after signing it, both sides violated the agreement.

Representatives of Russia, Ukraine, the Organization for European Security and Cooperation (OSCE), and leaders of two pro-Russian separatist regions, signed the Minsk 2 agreement in February 2015. The provisions of this agreement included, among other things, withdrawal of foreign troops and military equipment from Ukraine, return of control over the state borders to the Ukrainian government, exchange of prisoners and elections in Donetsk and Luhansk. Most of those provisions were never implemented. Russia claimed that it was not obliged to implement the agreement, denying its involvement in the conflict in eastern Ukraine.

Among the official narratives of Putin’s policy has long been the one on the alleged threat for Russia from the “expansionist” NATO which is trying to “encircle” Russia and thus threaten its security. Part of this narrative is an untrue story of the alleged NATO’s broken promise that “it will not expand to the east”. According to this, the accession of the former Warsaw Pact states to NATO is portrayed in the Russian media and political sphere as a threatening action of NATO, while the fact that states join NATO voluntarily and on their initiative is ignored.

Ever since Russia annexed Crimea in 2014 and organized and supported the rebel “republics” in the east, it has increasingly built a picture of Ukraine as a “puppet of the West”, justifying its military action and the occupation of a part of the territory, which Russia claimed it voluntarily acceded, and portraying it as practically self-defence moves.

In such a political and historical context, in December 2021, Russia demanded from the US and NATO allies that the former member states of the USSR be prevented from joining this alliance. This request also implied the withdrawal of NATO forces from Eastern Europe. The answer to this request was negative, with the emphasis that independent, sovereign states themselves decide whether they wanted to apply for membership in NATO.

At the time when Russia sent this request, it had already started troops build-up on the border with Ukraine, thus mounting an implicit threat of attack on this country if the request for a ban on NATO accession is not fulfilled. This was followed by warnings from NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg and US Secretary of State Antony Blinken that Russia intends to attack Ukraine, as well as calls to resolve border tensions diplomatically and without the use of force. Moscow, on the other hand, denied that it was planning to launch an invasion. Immediately before the start of the invasion, French President Emmanuel Macron and German Chancellor Olaf Scholz met with Vladimir Putin, while US Secretary of State Antony Blinken met with Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov in an attempt to reach a diplomatic solution and prevent the outbreak of war. These negotiations did not yield results.

After months of tension in the border areas, on February 21, 2022, Vladimir Putin signed a decision by which the Russian Federation recognized the independence of the Luhansk and Donetsk People’s Republics. This move was recognized as the most explicit expression of Putin’s intention to attack Ukraine, on whose borders there were already tens of thousands of soldiers. The warnings of Western officials came true just a few days later when on February 24, Russia began an open invasion of Ukraine by shelling numerous cities in this country.

Which narratives were the most represented in the domestic media?

An analysis of Raskrinkavanje’s database since the beginning of the war identified the six most prevalent narratives related to the Russian invasion.

The narrative whose goal is to shift the blame for the war from Russia to the West was tried to be “proven” with a number of pieces of disinformation. Most often, it included claims related to the alleged threat that the expansion of the NATO alliance represented for Russia, allegations about “Western support for Ukrainian Nazis”, but also claims about the alleged ethical decadence of the West and the superiority of Russia.

Similarly, the narrative about alleged chemical, nuclear and biological weapons that Ukraine possesses was also spread. Although there is no evidence of that, some domestic media published claims, mostly originating from Russia, that Ukraine is developing such weapons that could target and destroy Russia.

On the other hand, the narrative glorifying Russia with Putin at the helm, as well as the Russian army and the weapons it possesses, was also very prominent. Russia, Putin and the Russian army were portrayed as superior to Ukraine and the rest of the world, while at the same time, the crimes committed by this army were completely denied.

Among the various disinformation about the war in Ukraine, those that stood out were the allegations of widespread Nazism in that country and Russia’s efforts to “denazify” it. Thus, as part of the second narrative we analyzed, Ukraine was often accused of crimes it did not commit.

With the introduction of sanctions against Russia and its countermeasures, a narrative developed that dealt with their impact on Russia itself, but also on the West, which introduced the sanctions. According to this narrative, the sanctions imposed on Russia do not negatively affect it, but even strengthen it, while, on the other hand, the countries that have imposed sanctions on Russia suffer significant consequences.

Finally, the sixth narrative that we analyze in this series refers to accusing the Western and Ukrainian media of publishing fake news regarding the Russian invasion. In the local language region, various claims were spread that the Western media had completely invented certain news, often building on the war propaganda from the 1990s when the same claims were used to deny war crimes, described as “staged by Western media”.

In the coming days, you can read the analyses of those narratives on this link.

(Marija Ćosić and Tijana Cvjetićanin, Raskrinkavanje.ba)