Photo: Raskrinkavanje.ba

Russian media and sources on social networks regularly publish fabricated “news” that they attribute to Western or Ukrainian media to portray their reporting of the war in Ukraine as propaganda.

A photo of a woman with a bandage on her head and a destroyed building in the background made headlines around the world on February 24. Wounded Olena Kurilo was photographed by Wolfgang Schwan after air strikes of the Russian army in the city of Chuguev on the first day of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The photo taken for the Anadolu Agency was then published by numerous media in the world reporting on the Russian attack on this country.

Her photo soon started appearing on Facebook and Twitter for completely different reasons. Namely, numerous posts claimed that the photo was taken in 2018, that it shows a woman injured after the explosion of a gas cylinder, and that the “Western propaganda” is using it to create a false image of the war in Ukraine.

The disinformation about this photo was among the first fake news about the Western media reporting on the Russian invasion of Ukraine – a practice regularly used by the Russian side. The claims about it are not true, but they certainly raised at least some doubt among users of social networks regarding the reports of the Western media about the war in Ukraine. Some, however, accepted them without any verification as another “proof” of Western propaganda about the war in Ukraine.

New claims and the old narrative about “lies from the West”

Russian sources on social networks, as well as the media, have repeatedly published fake news attributed to “Western” or Ukrainian media, intending to discredit them. Fake screenshots are often created for this purpose, with the aim to prove that scenes from movies, or photos that have nothing to do with the war in Ukraine, are used “in the West”. In the past 11 months, such fake news has been the subject of Raskrinkavanje’s analyses 10 times.

The motivation for creating such fake news is questioning the credibility of Ukrainian and foreign media and to portray them as non-objective, unreliable and prone to spreading propaganda. This consequently leads to public confusion and loss of trust in the media due to contradictory messages and information in media reports. In this way, it becomes easier to promote Russian propaganda messages.

The most common targets of such disinformation are prominent Western media. In the posts rated by Raskrinkavanje, the alleged distribution of fake news was most often attributed to CNN, the BBC, the Financial Times and the Italian television TGCOM24, and sometimes to “Western media” in general. However, the creators of such fake news did not leave out the Ukrainian media either.

The essence of this discourse is the old narrative according to which media companies, mainly those from the United States and countries of Western Europe that have a global audience, spread fake news about world events – including reports about supposedly non-existent war crimes. The goal of the West, it is claimed, is to present the “political opponents” negatively and to justify its alleged imperialist aspirations.

Depending on the need, the narrative of the Western media’s propaganda reporting was adapted and used wherever it was needed to “shape” public opinion in wartime circumstances – from Syria to Yugoslavia. In the case of Russia, which is its biggest promoter, this narrative undoubtedly follows Moscow’s efforts to influence events and expand its influence on the global level. Thus, even unrelated to the war in Ukraine, it was often a tool used by Russia to discredit the Western media, accusing them of sacrificing the truth for the official interests of the United States and NATO.

One example of spreading this narrative is fake news about CNN that was spread by Russian sources on social media back in 2016. These posts claimed that CNN had faked reporting on the war in Syria, showing the same girl as the victim of various attacks by Assad’s army. But all of the three photos presented as proof of this false claim were taken in the same place at the same time and were never used by CNN to illustrate three different events.

In the BCS language region, this narrative was often linked to war propaganda from the 1990s, when the same claims were used to deny war crimes, which were claimed to have been “staged by the Western media”. Numerous articles in the pro-Russian media read today that we are seeing “the same scenario” (unjustly blaming Russia for the attack on Ukraine) that existed “also in the wars in the former Yugoslavia, where the Serbs were sole culprits”, as was stated in an article aptly titled Western “mirror propaganda”: The defeat of Kyiv has become inevitable, published on Pečat news website.

As baseless as it may be, the “Western media lies” narrative serves the purpose for which it was put forth. Accusing the Western media of spreading alleged fake news, the Russian media, which present themselves as promoters of truth, become the real source of fake news. The disinformation that is the subject of this analysis shows that it is Russian media, not the Western, that are on the mission of defending the official government policies.

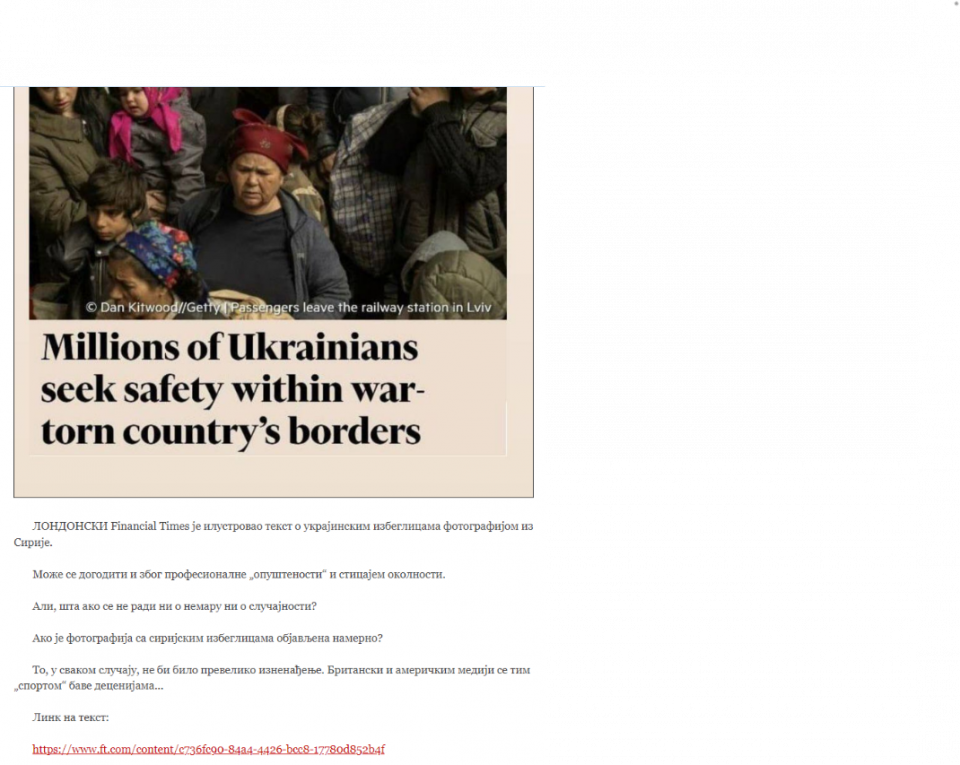

Allegations of pro-Russian or Russian state media that have been repeatedly documented to publish disinformation (such as Fakti or Sputnik) about the unprofessionalism or manipulativeness of the Western media are especially ironic when they appear in articles that are fake news themselves. Thus, for example, in an article in which it incorrectly claims that the Financial Times “portrayed Syrian refugees as Ukrainian”, Fakti news website sarcastically notes that the British and American media “have been engaged in the ‘sport’ of inventing fake news for decades”. Sputnik Srbija, on the other hand, in an article titled “How Western lies brought the world to the brink of conflict” laments over (Western) journalism, wondering if it died “in the latest crisis between Russia and the West or in the 1990s in the Balkans”.

Old or new photos?

The photo of the injured woman mentioned earlier is just one example of attempts to discredit the Western media on social networks, with the claims that they are using photos that have nothing to do with the war in Ukraine to “slander” the Russian side. This is not an isolated example.

There is a similar claim that CNN presented the explosion in Kyiv in 2015 as a picture of current events in Ukraine. In this case as well, the statements that the photo is old are incorrect. The Financial Times was also the target of such disinformation, as already mentioned.

Although most of this kind of fake news was published at the beginning of the war, the practice of discrediting the Western media based on this model was also noted in the later months of the invasion.

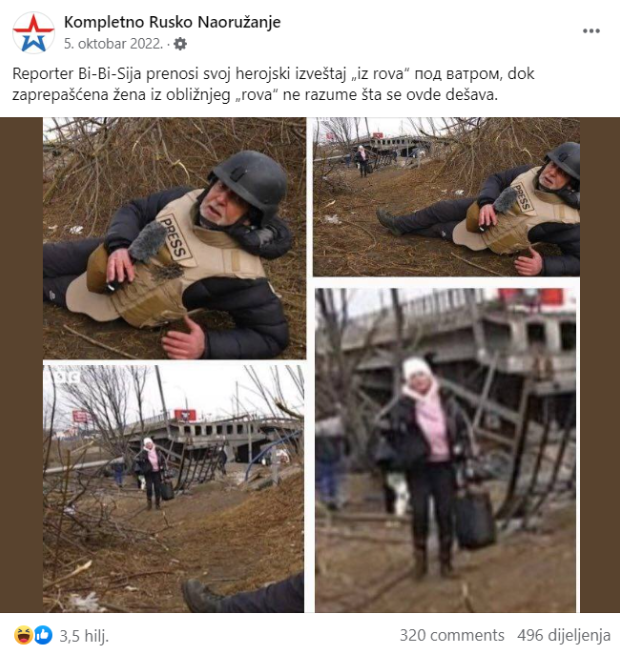

Thus the screenshots from a BBC report, initially broadcast in March, became viral in October when they were paired with the false claim that the BBC journalist Jeremy Bowen faked a war scene and exaggerated the danger he was in while reporting on the war operations in Irpin. The post on Facebook page “Kompletno Rusko Naoruzanje” had over 4,000 interactions, and it was also posted by the Embassy of the Russian Federation in Bosnia and Herzegovina on its official Facebook page.

News that the Western media never published

In the aforementioned cases, the creators of fake news intended to discredit the Western media by claiming that they are using old photos when reporting on the war in Ukraine. But this is just one pattern of “making up fake news”. In another one, which also appears often, there is an attempt to create the impression that the Western, or sometimes the Ukrainian media, published something that they did not. Screenshots of such disinformation content often carry logos of Western media companies to make everything look more convincing, and as a rule, they are almost absurd stories, whose task is to illustrate the alleged unprofessionalism and propaganda of the Western media.

One example of such disinformation is the claim that CNN posted twice on its Twitter profiles that the same journalist had been killed – first in Kabul and then in Ukraine. Then, side by side, a screenshot of a post from the Twitter profile of “CNN Ukraine” was shared, in which it is claimed that Bernie Gores was killed in Ukraine, and a screenshot of the profile of “CNN Afghanistan” where it is stated that he was killed in Kabul. Both profiles are fake, as was journalist Bernie Gores – the photo actually showed YouTuber Jordie Jordan.

Similarly, the Italian television station TGCOM24 was accused on social networks of using a scene from the American film “Deep Impact” from 1998 in a report on the war in Ukraine. TGCOM24 TV never published such an image in a report on Ukraine, just as the Western media never presented footage from Beirut in 2020 as footage from Ukraine, as some social media profiles claimed.

To support accusations of spreading Ukrainian and NATO propaganda, the promoters of this narrative also used a video showing the bombing of Paris, made by a French producer with the help of special effects, in order to appeal for a ban on flights over Ukraine.

In some regional media and sources on social networks, fake news was created about Western media that connected the war in Ukraine with the situation in the Balkans. On the very first day of the Russian invasion, disinformation appeared that CNN showed a map in a live program on which the border between Kosovo and Serbia was erased. There was actually a dotted line on the map. The goal of the creators of this fake news was not to inform the public truthfully but to show that the alleged erasure of the border was a direct result of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Twitter trolls as “Ukrainian propagandists”

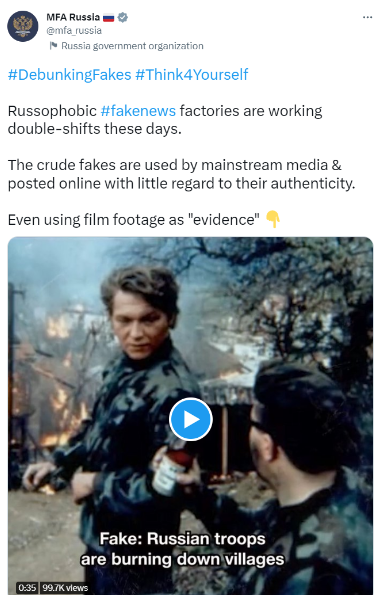

Shortly after the start of the invasion, social networks in the region were flooded with screenshots of a tweet that showed actor Dragan Bjelogrlic in a scene from the movie “Lepa sela, lepo gore” with a description in English that stated the following: “Russian occupation soldiers drink beer after burning a village. European civilisation is disappearing in flames”.

The post also included some of the hashtags used on Twitter for news from the attacked Ukraine – #StopPutin #StopRussia #StandingWithUkraine and #PutinHitler.

The picture was soon published by web portals Kurir and Srbin info, and was widely shared on Twitter and Facebook as evidence of “Ukrainian propaganda” that allegedly invents Russian crimes in Ukraine.

However, contrary to claims that these posts were made by “mainstream” media or “Ukrainian propagandists”, its actual author was a user from Serbia. The author was one of the “internet trolls” who produced such content to ridicule or discredit real reports about the attacks on Ukraine.

Bjelogrlic was not the only Serbian actor who was shown on Twitter as being involved in “fighting” in Ukraine. Nikola Kojo was presented as a “hero from Ukraine”, and Rados Bajic as the “Ghost of Kyiv” – a Ukrainian pilot who was claimed to have shot down six Russian planes. They were also created by “trolls” who tweet in Serbian and English, and who posted these tweets to deceive other users on the Internet, or as a form of bizarre satire.

“Trolling” was also quickly used by the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which published a photo featuring Bjelogrlic on its Twitter account, with the claim that it represents an extraordinary effort by “Russophobic fake news factories” whose “crude” products are used by the mainstream media regardless to their authenticity.

Social network users, media and official institutions: everyone on the mission

With the exception of a couple of examples, such as the fake news that CNN showed a map on which the border between Kosovo and Serbia was erased, and tweets in which actors from Serbia were presented as soldiers, all of the mentioned fake news was created outside the BCS language region, and in most of the cases also shared in other languages.

Most of them came from Russian media or social media sources. For example, fake news about the cover of the Financial Times was published on the Telegram channel of Margarita Simonian, editor of the Russia Sevodnja news agency and RT television.

Official Russian institutions also contributed to the spread of this propaganda narrative.

The Embassy of the Russian Federation in Bosnia and Herzegovina has published photos of Jeremy Bowen, a BBC journalist, with explicit claims that they are evidence of “staging” and an example of “Western propaganda”.

In the BCS language region, these fake news mostly appeared first on social networks, and then they were published by some regional media. The list of media includes, among others, Informer, Kurir, Sputnik, Alo online, Glas javnosti and Srbin info from Serbia, Croativ from Croatia and ATV from Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Deutsche Welle, which was also the target of such disinformation, wrote about the phenomenon of the spread of fake news attributed to Western and Ukrainian media. When it comes to this practice in the context of the war in Ukraine, DW’s interlocutors point to possible organized and coordinated action.

Experts believe that the clues leading to the real authors of fake videos, photos or tweets are not always obvious, but they do lead to Russia. Josephine Lukito, a professor at the School of Journalism and Media at the University of Texas at Austin, sees the glimpse of the professional structures behind the fake productions. Much of the pro-Russian disinformation can be attributed to the Internet Research Agency (IRA), a Russian troll factory that has been active since 2012. The IRA gained notoriety for attempting to influence the 2016 US presidential campaign. Since 2014, numerous false reports, attributed to the IRA, have been spreading about Ukraine.

The practice of “planting” fake news in the previously described way is somewhat of a new phenomenon, connected to the emergence of social networks and the relative availability of various tools that enable the creation of seemingly credible “evidence” such as screenshots and other types of manipulation. Although it was used earlier, it seems to have been especially popularized with Russia’s attack on Ukraine, when Russian propaganda saw it as a chance to create receptive, more or less convincing “evidence” for old claims about unprofessional and unobjective Western media.

(Marija Manojlović, Raskrinkavanje.ba)